The Improbable exists wholly due to the passion and good will of booksellers who give their time to write about books that intrigue them, that are not easy to describe or summarize, that provoke more questions than answers. In this latest issue, one of those pervasive questions seems to address the act of reading itself: how do I read this? Reading is an act governed by transparent conventions that most of us, most of the time, never give pause to think about. We follow words and images left to right, top to bottom, on screens and printed pages, that we understand have literal correspondences and intend specific meaning.

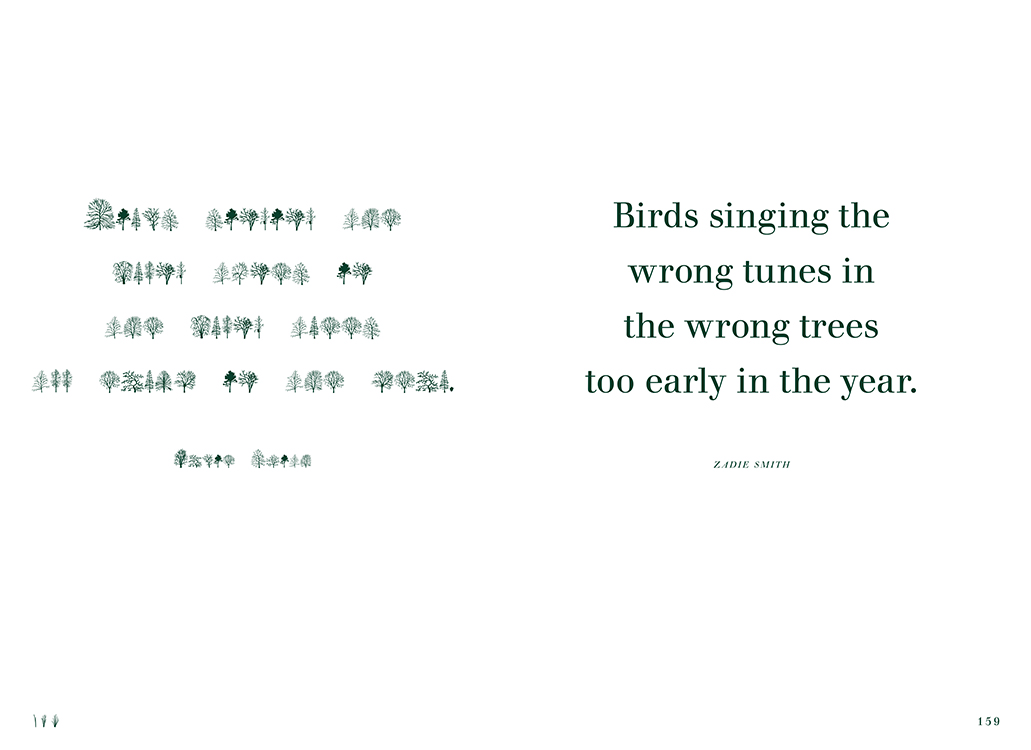

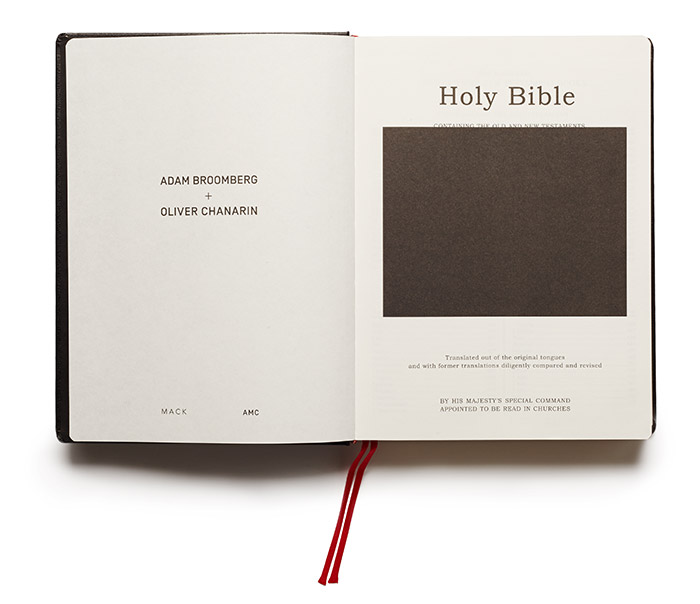

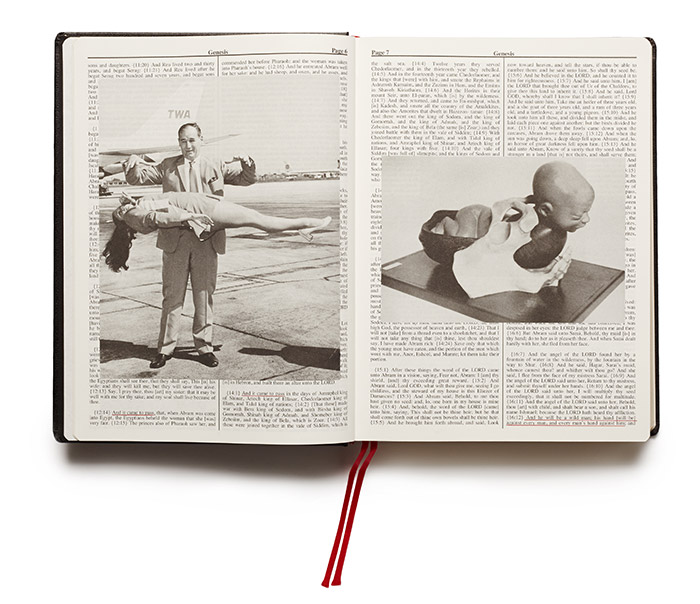

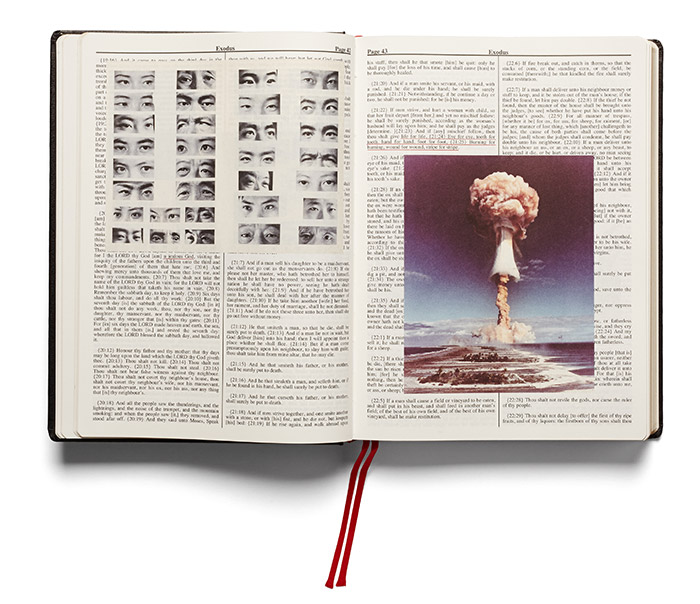

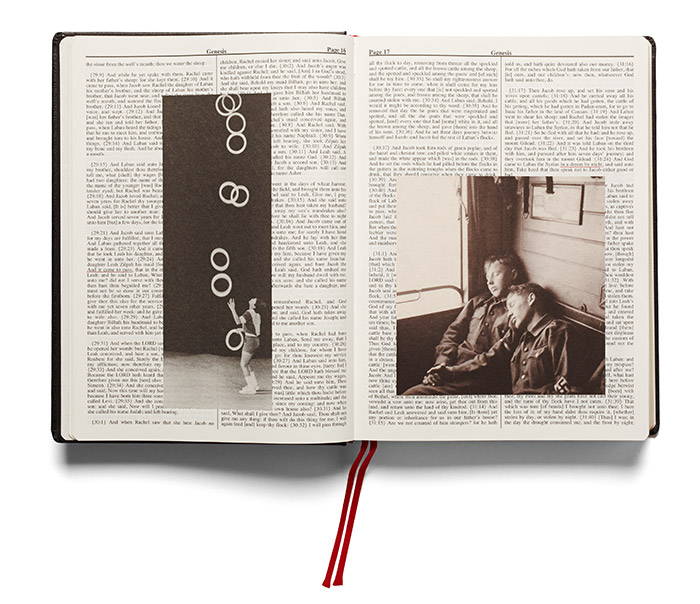

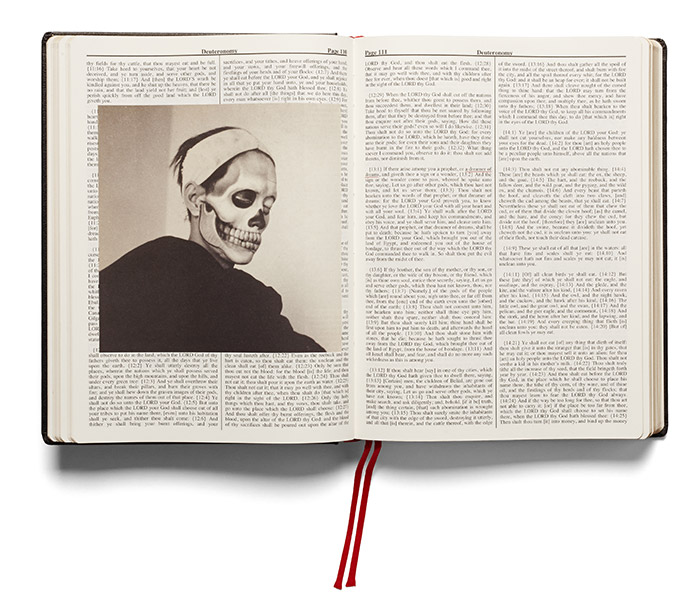

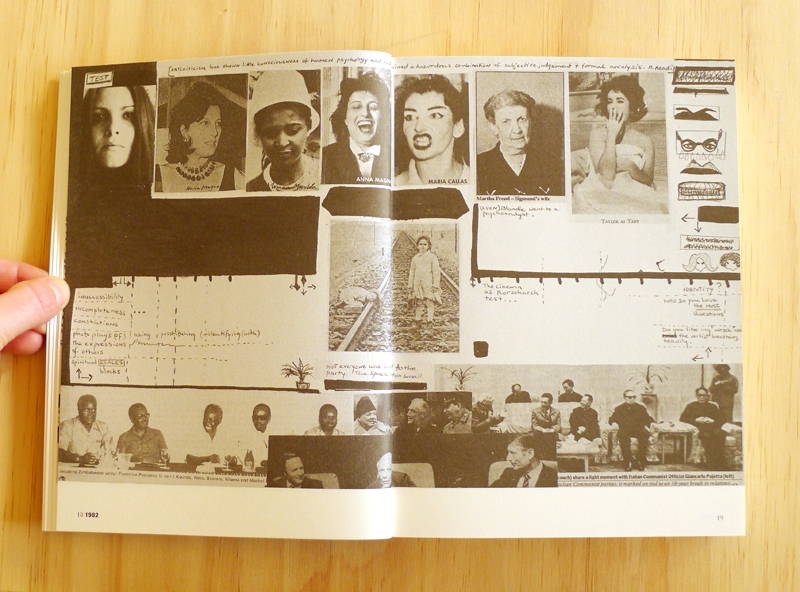

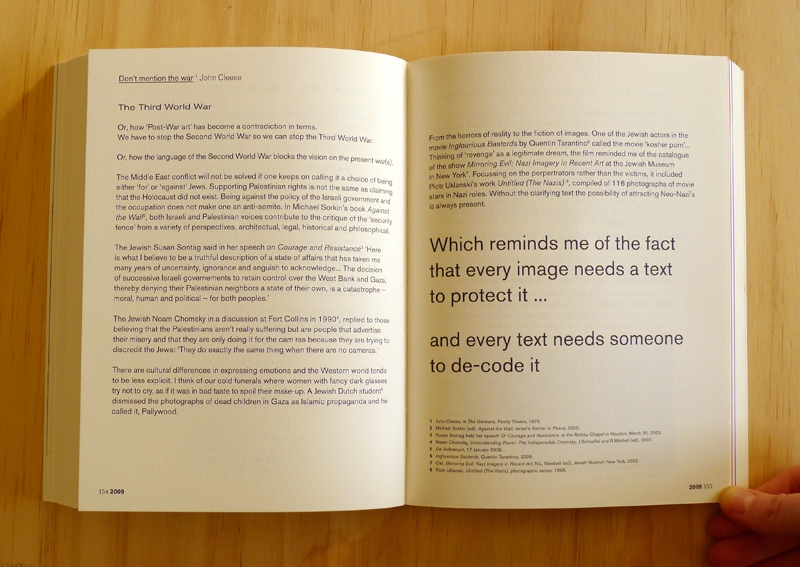

But the 19th century French poet Stéphane Mallarmé used words and the space of the page in ever radical ways in Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard, translated now by Robert Bononno and Jeff Clark and published as A Roll of the Dice by Wave Books. In both the original and this new translation, literal correspondences implode; the boundaries of the page are violated. So too in Oliver Chanarin and Adam Broomberg's Holy Bible (published by MACK), a collage work that interrogates the relationship between violence and the divine by juxtaposing contemporary images with the entirety of the bible. In this issue of The Improbable, our reviewers discuss books in which readers are invited to read in tree, a new alphabet conceived by poet Katie Holten (About Trees, Broken Dimanche Press), to read between the images in South African artist Marlene Dumas's notebooks (Sweet Nothings, Walther König), and to read into a world in which all traditional paradigms are questioned, probed, and turned inside out in Maggie Nelson's The Argonauts (Graywolf). While this last book is not a visual-literary hybrid like most other books reviewed in The Improbable, it is a wholly uncategorizable book about what it means to live an uncategorizable life. The Improbable seems like the perfect place for it.

This is now the opportunity to thank our newest reviewers—Emma Wippermann at Book Thug Nation (Brooklyn), Simon Crafts at Alley Cat Books (San Francisco), and Clark Allen at Skylight Books (Los Angeles)—and our veterans, Katie Eelman from JP Papercuts, and Stephen Sparks from Green Apple whom we're particularly lucky to have writing and advocating for The Improbable.

You may have noticed that The Improbable took a somewhat long summer hiatus. This is due to the fact that The Improbable is produced by Siglio which means, as a one-person operation, my attention is most often diverted to bringing another handful of these unusual books into the world. That said, Siglio is possible only when connections between books, booksellers, and readers are forged, and Siglio is committed to a fertile landscape in which other independent publishers taking these same kinds of risks have the opportunity to make and sustain these connections too. All this depends ultimately on you, the reader and the bookseller, to demonstrate your own particular passion for the books you love—and for the cultivating a cultural landscape in which books like these thrive. I hope you'll help us by spreading the word about any book you discover here and about The Improbable as a special place to discover them.

—Lisa Pearson